Editor's note: Elizabeth Warren, a US Senator running for president, recently released an anti-corruption plan. Read this explainer to understand what she means by “corruption” and to consider whether such a plan would work.

We all love a good game. Some like sports, video games, tabletop games, party games, or all of the above. But, what if a player cheats? That is the quickest way to ruin any game. So, what if some people cheat in the game of life? According to Senator Elizabeth Warren that is exactly what is happening in America today.

Why Everyone Opposes Corruption

In soccer, a team might cheat by paying a referee to ignore a foul. We call that a bribe. The bribe destroys the purity of the game, like toxic waste leaking into a beautiful lake. The cheating team and the referee would be considered “corrupt” and the game itself “corrupted.”

Similarly, according to Senator Warren, wealth is corrupting our democracy.

America needs lots of big changes to improve the lives of its people. Senator Warren, for her part, thinks the government should provide free universal health care and free universal college. And in order to pay for such large programs, she believes we need to more heavily tax the wealthy.

The problem, according to Senator Warren, is that wealthy people and corporations are blocking such policies by using their money to influence the government. This is called “lobbying,” and it is currently legal, for the most part. But many people think it is basically bribery, and Senator Warren calls it corruption. By blocking certain reforms, that corruption may benefit the wealthy few, but harm ordinary Americans.

As Senator Warren put it in her own words:

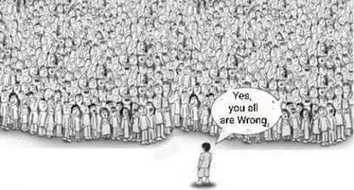

Look closely, and you’ll see — on issue after issue, widely popular policies are stymied because giant corporations and billionaires who don’t want to pay taxes or follow any rules use their money and influence to stand in the way of big, structural change.

We’ve got to call that out for what it is: corruption, plain and simple. [emphasis in original.]

Senator Warren wrote these words in a Medium.com article titled “My Plan to End Washington Corruption,” which announced:

…a comprehensive set of far-reaching and aggressive proposals to root out corruption in Washington. It’s the most sweeping set of anti-corruption reforms since Watergate. The goal of these measures is straightforward: to take power away from the wealthy and the well-connected in Washington and put it back where it belongs — in the hands of the people. [emphasis in original.]

As Vox.com recently reported, the plan’s biggest target is lobbying:

Warren’s most recent anti-corruption plan contains nearly 100 proposals to change how lobbying works in all three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. It’s modeled after the Anti-Corruption and Public Integrity Act she introduced last summer but contains some major changes.

There is widespread disagreement over whether universal health care, universal college, etc, will make matters better or worse for ordinary Americans. But most agree that corruption is bad. But is lobbying corrupt? Some argue no, not always. But let’s assume that some lobbying is corrupt. Will Senator Warren’s restrictions on lobbying cure Washington corruption, as she promises?

When looking for a cure, you want to attack the disease, and not just a symptom. After all, Tylenol is no cure for brain cancer. So, what if lobbying is only a symptom and not the root cause of corruption?

As the journal Issues and Insights recently reported:

Writing in the Global Anticorruption Blog, Harvard law professor Matthew Stephenson says several studies have found a clear correlation in the U.S. between the size of state governments and corruption.

“Within the U.S., when controlling for a number of other economic and demographic factors, states with larger public sectors seem to have higher corruption,” he writes.

A 1998 study, for example, shows “government size, in particular, spending by state governments, does indeed have a strong positive influence on corruption.”

A 2012 study, titled “Live Free or Bribe,” looked at the number of government officials convicted in a state for crimes related to corruption and found that the more economic freedom there was in the state, the less corruption resulted.

“Economic freedom,” the study found, “has a negative impact on corruption.”

These studies point to two possible root causes of corruption: the bigness of government and the smallness of economic freedom.

Cutting Back Corruption

Why might less economic freedom lead to more corruption? Well, if you have fewer ways to earn money honestly, then dishonest ways may become more tempting.

And why might bigger government lead to more corruption? Let’s think back to sports.

Imagine if a referee didn’t just enforce the rules, but could create new rules mid-game, even if the new rules gave some teams and players an advantage over others. Such an “uber-ref” would have the power to basically pick winners and losers.

Maybe the ultimate anti-corruption plan is freedom.

Who would be more tempting to bribe? A regular ref who can nudge things your way by making bad calls here and there? Or an uber-ref who can tilt the whole playing field your way by making “big, structural changes” to the game?

Similarly, the bigger the government is, the more power it has to “rig the game of life,” and the more tempting it is to “bribe,” whether legally (lobbying) or illegally (cash payoffs).

In other words, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” as a smart guy said over a century ago. Government power enables cheating, and nothing ruins a game like cheating. (For details on how this happens in real life all the time, check out FEE’s resources on “cronyism.”)

All this may be problematic for Senator Warren. The whole point of her anti-corruption plan is to remove obstacles to the “big, structural change” she wants to make as president. But her policies’ main themes are that they involve (1) the growth of government, and (2) the shrinkage of economic freedom, both of which, as we have covered, may very well boost corruption.

Senator Warren’s anti-corruption plan may attack a symptom of corruption, while neglecting—perhaps even feeding—the underlying disease.

What’s the alternative? Well, if the above studies are onto something, maybe our government should be less like an uber-ref and more like a regular referee, enforcing basic rules against “fouls” (like fraud and theft) instead of creating huge new ones all the time. That might discourage cheating by giving lobbyists less to lobby for, and encourage fair play by letting businesses be free to do honest business.

Maybe the ultimate anti-corruption plan is freedom.